Module Mayhem : Python

By now you’ve got the basics of Python down and you’ve managed not to get eaten by the snake, so congrats. Now we’re going deeper into its territory: modules, packages, and pip.

Module

Module is a decomposition process of breaking down a complex problem or a system into smaller, independent components. It is a file containing Python definitions and statements, which can be later imported and used when necessary.

The Python Standard Library contains built-in modules (written in C) as well as modules written in Python.

Importing a module

1

2

3

4

5

import math

from math import sin, pi

from module import *

import module as alias

from module import name as alias

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

# Example

from math import sin, pi

print(sin(pi / 2))

pi = 3.14

'''redefine the meaning of pi and sin - in effect, they supersede the original (imported) definitions within the code's namespace'''

def sin(x):

if 2 * x == pi:

return 0.99999999

else:

return None

# Output:

1.0

0.99999999

Working with standard module

math

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

import math

for name in dir(math):

print(name, end="∖t")

# Output

__doc__ __loader__ __name__ __package__ __spec__ acos acosh asin asinh atan atan2

atan2 atanh ceil copysign cos cosh degrees e erf erfc exp expm1 fabs factorial floor

fmod frexp fsum gamma hypot isfinite isinf isnan ldexp lgamma log log10 log1p

log2 modf pi pow radians sin sinh sqrt tan tanh trunc

random

If computer is 100% deterministic. How does random.randint(1,10) sometimes give 3, sometimes 7?

It’s fake randomness (called pseudo-random).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

import random # ← At this exact moment, Python secretly does:

# random.seed() with a value based on the current clock/time

print(random.getstate()) # Huge blob of data = current seed state

# Run the script again → the blob will be different!

random.seed(42) # Force the seed to be 42

print(random.randint(1, 100)) # → always 81

print(random.randint(1, 100)) # → always 14

print(random.randint(1, 100)) # → always 3

# Try running the whole script again → you get 81, 14, 3 again!

1

2

3

4

5

import random

dir(random)

# Output

['BPF', 'LOG4', 'NV_MAGICCONST', 'RECIP_BPF', 'Random', 'SG_MAGICCONST', 'SystemRandom', 'TWOPI', '_ONE', '_Sequence', '__all__', '__builtins__', '__cached__', '__doc__', '__file__', '__loader__', '__name__', '__package__', '__spec__', '_accumulate', '_acos', '_bisect', '_ceil', '_cos', '_e', '_exp', '_fabs', '_floor', '_index', '_inst', '_isfinite', '_lgamma', '_log', '_log2', '_os', '_pi', '_random', '_repeat', '_sha512', '_sin', '_sqrt', '_test', '_test_generator', '_urandom', '_warn', 'betavariate', 'binomialvariate', 'choice', 'choices', 'expovariate', 'gammavariate', 'gauss', 'getrandbits', 'getstate', 'lognormvariate', 'normalvariate', 'paretovariate', 'randbytes', 'randint', 'random', 'randrange', 'sample', 'seed', 'setstate', 'shuffle', 'triangular', 'uniform', 'vonmisesvariate', 'weibullvariate']

platform

1

2

3

4

5

import platform

dir(platform)

# Output

['_Processor', '_WIN32_CLIENT_RELEASES', '_WIN32_SERVER_RELEASES', '__builtins__', '__cached__', '__copyright__', '__doc__', '__file__', '__loader__', '__name__', '__package__', '__spec__', '__version__', '_comparable_version', '_default_architecture', '_follow_symlinks', '_get_machine_win32', '_java_getprop', '_mac_ver_xml', '_node', '_norm_version', '_os_release_cache', '_os_release_candidates', '_parse_os_release', '_platform', '_platform_cache', '_sys_version', '_sys_version_cache', '_syscmd_file', '_syscmd_ver', '_uname_cache', '_unknown_as_blank', '_ver_stages', '_win32_ver', '_wmi_query', 'architecture', 'collections', 'freedesktop_os_release', 'functools', 'itertools', 'java_ver', 'libc_ver', 'mac_ver', 'machine', 'node', 'os', 'platform', 'processor', 'python_branch', 'python_build', 'python_compiler', 'python_implementation', 'python_revision', 'python_version', 'python_version_tuple', 're', 'release', 'sys', 'system', 'system_alias', 'uname', 'uname_result', 'version', 'win32_edition', 'win32_is_iot', 'win32_ver']

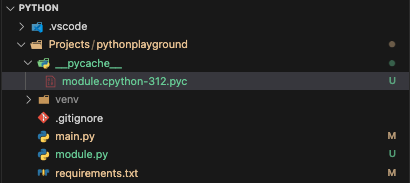

How module works?

If you create module, lets say module.py and import it to main.py, a new subfolder appears - __pycache__. It has a file called module.cpython-xy.pyc where x and y are digits derived from python version. The last part .pyc comes from the word Python and Compiled. It is a byte code ready to be executed by interpreter.

The famous if __name__ == "__main__": guard

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

# module.py

print("I like to be a module.")

print("My __name__ is:", __name__)

# This part runs ONLY when you run module.py directly

if __name__ == "__main__":

print("I'm being run directly! Let's do some tests:")

print("Testing my own functions...")

else:

print("I was imported by another module")

1

2

3

4

5

# Output

I like to be a module.

My __name__ is: __main__

I'm being run directly! Let's do some tests:

Testing my own functions...

Let’s say you import module.py to your main.py and run the main.py script, the output will be:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

import module

print(__name__)

# Output

I like to be a module.

My __name__ is: module

I was imported by another module

To sum it up, if you run the module directly, __name__ becomes "__main__" and the statements in if __name__=="__main__": runs. If it is imported to main.py and you run main.py, __name__ becomes "your file name" and if __name__=="__main__": doesn’t run.

Real World Example

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

# calculator.py

def add(a, b):

return a + b

def subtract(a, b):

return a - b

# These tests run only when you execute this file directly

if __name__ == "__main__":

print("Testing calculator...")

print(add(5, 3)) # → 8

print(subtract(10, 4)) # → 6

Private variable

Please don’t touch !

Python has no real private keyword like Java/C++ . It doesn’t stop you from touching “private” things- it just asks nicely with underscores.

_var→ “please don’t touch this unless you have a good reason”__var→ “I really don’t want you to touch this (but you still can if you try hard)”

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

# module.py

counter = 0 # public – anyone can touch

_counter = 0 # "protected" – gentle warning

__counter = 0 # "private" – name mangled

def incr():

global counter, _counter, __counter

counter += 1

_counter += 1

__counter += 1

print("Inside module, __counter is:", __counter)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

# main.py

import module

module.incr()

print(module.counter) # → 1 works

print(module._counter) # → 1 works, but you’re being rude

# print(module.__counter) # → AttributeError!

# But... Python actually renamed it!

print(module._module__counter) # → 1 the secret way to access it

This name mangling (_module__counter) is Python’s tiny attempt to protect you from accidental access — but anyone who knows the trick can still get in.

The Shebang Line

1

#!/usr/bin/env python3

“When someone runs this file as an executable, please use

/usr/bin/env python3to launch it.”

What if module and main are in different folders ?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

C:\Users\user\py\

│

├── modules\

│ └── module.py ← our reusable module

│

└── progs\

└── main.py ← wants to import module.py

Since module is not in the where main is, main.py will crash. We will look into packaging our module later, first lets look at adding modules folder to sys.path during runtime.

Method 1: Modify the sys.path

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

import sys

from pathlib import Path

sys.path.insert(0, str(Path(__file__).resolve().parent.parent))

# sys.path.append(str(Path(__file__).parent.parent / "modules"))

''' sys.path.append(...) appends at the end, lower priority

sys.path.insert(0, ...) inserts at beginning and highest priority'''

Visual Diagram of sys.path.insert(0, …)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

# How sys.path.insert(0, str(Path(__file__).resolve().parent.parent)) works

main.py ──→ __file__ = "C:/.../py/progs/main.py"

↓

Path(...) → Path object

↓

.resolve() → absolute path

↓

.parent → progs folder

↓

.parent → py folder (project root)

↓

str(...) → "C:\\Users\\user\\py"

↓

sys.path.insert(0, ...) → added at the front

↓

import module → FOUND in C:\Users\user\py\modules\

Visual Diagram of sys.path.append(…)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

main.py (currently running)

│

▼

__file__

= "C:/Users/user/py/progs/main.py"

│

▼

Path(__file__) ──▶ WindowsPath('C:/Users/user/py/progs/main.py')

│

▼

.parent ──▶ C:/Users/user/py/progs

│

▼

.parent ──▶ C:/Users/user/py ← project root

│

▼

/ "modules" ──▶ C:/Users/user/py/modules ← target folder!

│

▼

Path(__file__).parent.parent / "modules"

│

▼

str(...) ──▶ "C:\\Users\\user\\py\\modules"

│

▼

sys.path.append("C:\\Users\\user\\py\\modules") ← added to the END of sys.path

│

▼

Now this works! ──▶ import module # Python finds module.py

Method 2: Run as a module with -m

1

2

cd C:\Users\user\py

python -m progs.main

This tells Python

“Treat the

pyfolder as the root, and run themain.pyinside theprogspackage.”

For this to work, you may need to add an empty __init__.py in the progs folder (optional in Python 3.3+, but still good practice).

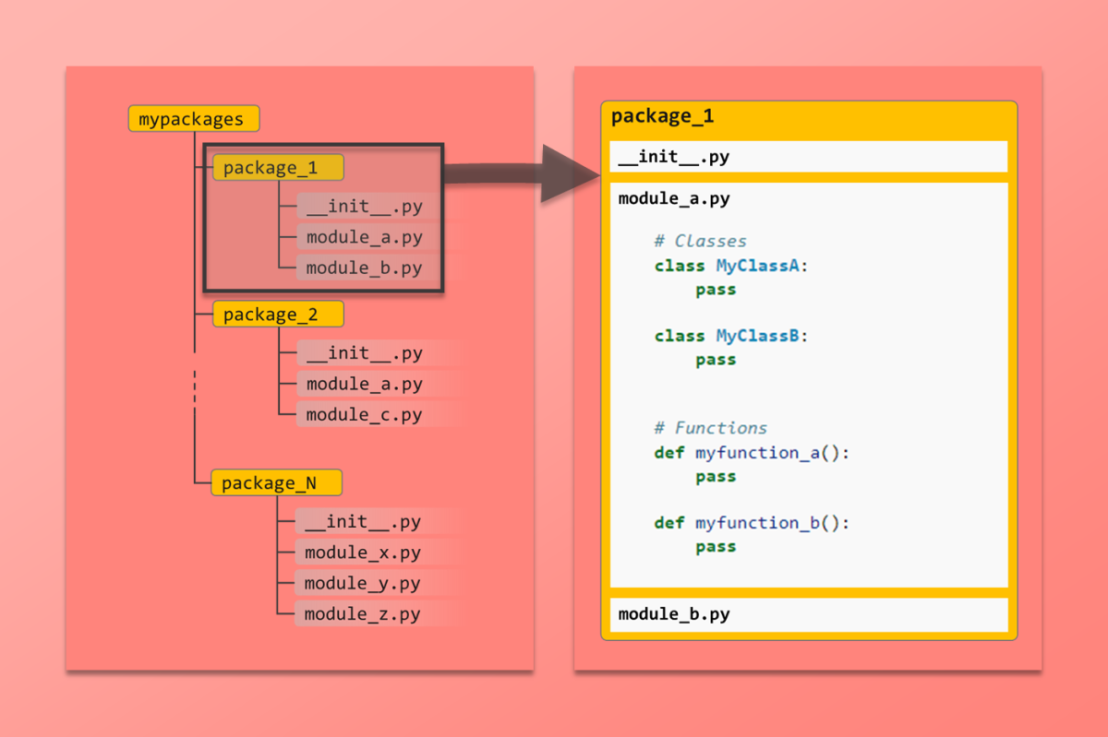

Package

A package is a bundle of modules.

__init__

“Hey Python, this folder is special – it’s a package!” You tell Python that by putting a tiny file called

__init__.pyinside it. The file can be empty, or it can contain shortcuts so people don’t have to type long names.

Example 1

1

2

3

4

test2/

└── utils/

├── __init__.py ← completely empty file!

└── hello. ← contains: def hi(): print("hi")

1

2

3

4

# main.py

import utils

from utils.hello import hi

hi() # → prints "hi"

Example 2

1

2

# utils/__init__.py

from .hello import hi # this is the only line

1

2

3

# main.py

import utils

utils.hi() # no need to write utils.hello.hi

__all__

What is __all__?

“When someone does

from utils import *, ONLY give them these things.”

Without __all__, Python gives everything that’s “public” (not starting with _). With __all__, you are the boss — only what you list gets in.

Example 3

1

2

3

4

5

6

# utils/__init__.py

from .hello import hi

from .math import add

from .colors import red

__all__ = ["hi", "add", "red"] # ← this line is the gatekeeper!

I will go into the details of packagename.toml later so no sys.path hack is required and no relative path nightmares - just pure, clean Python.

package.zip

We can still use the sys.path hack, if you want to. Also we can zip the package folder and use the path.append to add the package path.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

# test_zip.py

import sys

from pathlib import Path

# Add the zip file to Python's search path

sys.path.append(str(Path("package.zip")))

# These imports work directly from inside the ZIP!

import extra.iota as iot

from extra.good.best.sigma import funS

iot.fun1()

print(funS())

print("It worked from inside a ZIP file! No extraction needed!")

Python Package Installer (PIP)

Python Package repository https://pypi.org/ It is maintained by a workgroup named as Packaging Working Group, a part of Python Software Foundation. https://wiki.python.org/psf/PackagingWG

pip -pip installs packages, and the pip inside ‘pip installs packages’ means ‘pip installs packages’…..a recursive acronym.

1

2

3

sudo apt install python3-pip

python -m pip install --upgrade pip # To upgrade

1

2

3

4

5

6

# Check pip version

(venv) butcher@desktop:~/repo/python_notes$ pip --version

pip 24.0 from /home/butcher/repo/python_notes/venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages/pip (python 3.12)

(venv) butcher@desktop:~/repo/python_notes$ pip3 --version

pip 24.0 from /home/butcher/repo/python_notes/venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages/pip (python 3.12)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

(venv) butcher@desktop:~/repo/python_notes$ pip

Usage:

pip <command> [options]

Commands:

install Install packages.

download Download packages.

uninstall Uninstall packages.

freeze Output installed packages in requirements format.

inspect Inspect the python environment.

list List installed packages.

show Show information about installed packages.

check Verify installed packages have compatible dependencies.

config Manage local and global configuration.

search Search PyPI for packages.

cache Inspect and manage pip s wheel cache.

index Inspect information available from package indexes.

wheel Build wheels from your requirements.

hash Compute hashes of package archives.

completion A helper command used for command completion.

debug Show information useful for debugging.

help Show help for commands.

General Options:

-h, --help Show help.

--debug Let unhandled exceptions propagate outside the main subroutine, instead of logging them to stderr.

--isolated Run pip in an isolated mode, ignoring environment variables and user configuration.

--require-virtualenv Allow pip to only run in a virtual environment; exit with an error otherwise.

--python <python> Run pip with the specified Python interpreter.

-v, --verbose Give more output. Option is additive, and can be used up to 3 times.

-V, --version Show version and exit.

-q, --quiet Give less output. Option is additive, and can be used up to 3 times (corresponding to WARNING, ERROR, and CRITICAL logging levels).

--log <path> Path to a verbose appending log.

--no-input Disable prompting for input.

--keyring-provider <keyring_provider>

Enable the credential lookup via the keyring library if user input is allowed. Specify which mechanism to use [disabled, import, subprocess]. (default: disabled)

--proxy <proxy> Specify a proxy in the form scheme://[user:passwd@]proxy.server:port.

--retries <retries> Maximum number of retries each connection should attempt (default 5 times).

--timeout <sec> Set the socket timeout (default 15 seconds).

--exists-action <action> Default action when a path already exists: (s)witch, (i)gnore, (w)ipe, (b)ackup, (a)bort.

--trusted-host <hostname> Mark this host or host:port pair as trusted, even though it does not have valid or any HTTPS.

--cert <path> Path to PEM-encoded CA certificate bundle. If provided, overrides the default. See 'SSL Certificate Verification' in pip documentation for more information.

--client-cert <path> Path to SSL client certificate, a single file containing the private key and the certificate in PEM format.

--cache-dir <dir> Store the cache data in <dir>.

--no-cache-dir Disable the cache.

--disable-pip-version-check

Donot periodically check PyPI to determine whether a new version of pip is available for download. Implied with --no-index.

--no-color Suppress colored output.

--no-python-version-warning

Silence deprecation warnings for upcoming unsupported Pythons.

--use-feature <feature> Enable new functionality, that may be backward incompatible.

--use-deprecated <feature> Enable deprecated functionality, that will be removed in the future.

1

2

3

4

5

# Some useful pip commands

pip help install

pip list

pip show pip # shows installed packages

pip search anystring # can serach from web

Dependencies

Dependency Hell ? - Fortunately not. pip can do all of this for you.

Lets take this command pip show pip

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

(venv) butcher@desktop:~/repo/python_notes$ pip show pip

Name: pip

Version: 24.0

Summary: The PyPA recommended tool for installing Python packages.

Home-page:

Author:

Author-email: The pip developers <distutils-sig@python.org>

License: MIT

Location: /home/butcher/repo/python_notes/venv/lib/python3.12/site-packages

Requires:

Required-by:

This metadata has following last two lines:

- which packages are needed to successfully utilize the package (Requires:)

- which packages need the package to be successfully utilized (Required-by:)

pip install something

Normal

pip install pygame→ assumes you are an administrator and tries to write into system directories.pip install --user pygame→ the double dash--usertells pip: “Hey, I’m just a normal user, please put the package in my home folder instead.”

If you have created a virtual environment and enabled it (venv), you can ignore --user.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

# Some useful pip install / uninstall commands

pip install -U package_name # Update a locally installed package

pip install package_name==package_version # Install a user-selected version of a package (pip installs the newest available version by default)

# Eg: pip install pygame==1.9.2

pip unistall package_name